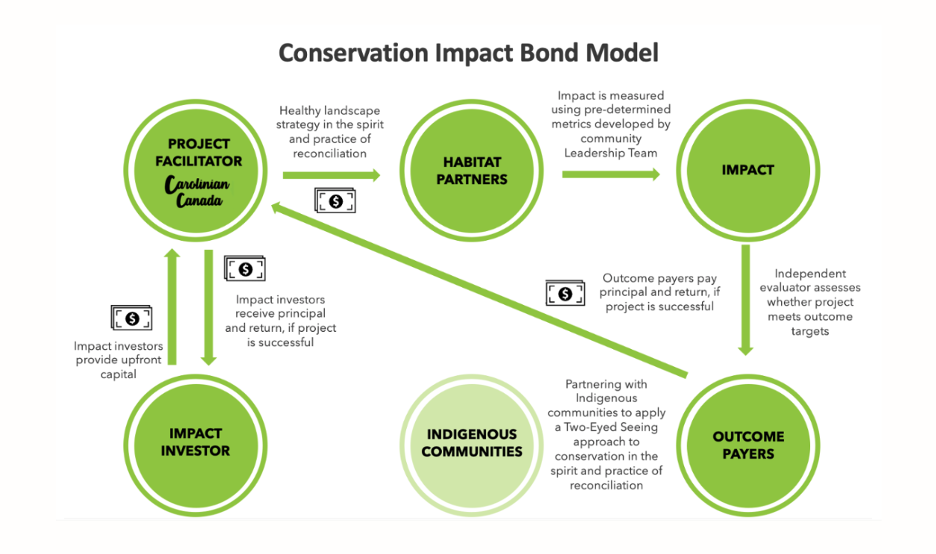

Deshkan Ziibi Conservation Impact Bond model (source DZCIB Story Map)

Part 3 of Bioregions as a Framework of Value

This is the third and last in our series of blogs that explore landscape-scale regeneration and how it can be accelerated. It is also a synthesis of our report “Bioregions as a Framework of Value” that is included in the r3.0 Blueprint Series 2019-2022 Blueprint 8: Funding Governance for Systemic Transformation. Hot off the digital press, the Blueprint is now on the r3.0 website and can be downloaded as a PDF here.

So far, we have covered the ecological, societal, economic and geo-systemic context for this work, what bioregioning as a practice has to offer, the range of ways in which finance is showing up to resource this work,and the yawning gap between aspirations and impact. Over this past summer of heat and drought, floods and loss of life, the urgency of understanding how to work regeneratively at landscape scale for climate adaptation became ever more apparent to us.

What also became increasingly clear was that while regenerative finance was the original impetus for the work, it is not where we have ended up. We are not alone in the conviction that none of this work is possible without a regeneration activator who acts as a trusted neutral player, a convenor, role-definer, meaning-maker, investment enabler, learning-leader and facilitator.

This organisation or person holds the space for collective visioning: bringing to life a vision of a dynamic and thriving ‘end state’ for the landscape or bioregion and its communities. This end state requires all actors to image a future together. Ideally one that challenges the current market trend of concentrating power, land and money into fewer and fewer hands. A concentration that is not helped by the new markets in carbon sequestration and biodiversity and nutrient gain.

The regeneration activator gives people a greater voice to critique how land is used, brings new entrants into food growing and farming (for example), and promotes ways to retain the wealth generated within the local region. An additional benefit is that relationships between people and the more-than-human-world can become explicit and co-evolving. This is why, when we were directed to take a look at the Deshkan Ziibi Conservation Impact Bond (DZCIB; see the graphic above) our eyes lit up.

The convening body of DZCIB have elegantly brought together many of the dimensions we now see as important to an evaluation process. Through the long and detailed process that they led landowners, project leaders, impact investors, conservationists and so called ‘outcome payers’ through, five evaluation pillars were agreed:

- connecting healthy habitats,

- connecting opportunities,

- connecting knowledge / circling and learning,

- connecting our hearts and minds, and

- connecting our bodies.

Our appreciation of the thinking behind DZCIB is partly born out of the fact that we speak from first-hand experience of inhabiting the regeneration activator role. Isabel is co-founder of the Bioregional Learning Centre in South Devon and Paul is a regenerative practitioner and systems change consultant focusing on the Bristol Avon Bioregion, both in England. We are seeing at first hand the need for landscape-scale decision-making, investment and regenerative actions in everything from farming and social care to manufacturing and tourism.

In Devon, the Bioregional Learning Centre led the collective that made the Devon Doughnut: an ecological and economic assessment of where Devon stands and how far it has to go in meeting the imperatives of planetary boundaries and social needs. In North Somerset Paul convenes a group in the City of Bath called ‘Bath in its Bioregional Economy’ which is co-creating a Story of Place to understand the City’s role in bringing a new regenerative economy to life. In sharing the diversity of experiences of the City, understanding is growing that the need for relationship building sits at the very heart of any move towards a regenerative and distributive economy.

Out of our work over the past five months on Bioregions as a Framework of Value, we have condensed these ten Principles for investing in landscape-scale regeneration

- None of this work is possible without a regeneration activator who acts as a trusted neutral player, a convenor, role-definer, meaning-maker and facilitator.

- Because climate change is already changing landscapes, investing in bioregion-scale processes that enable us to keep pace with change and learn for adaptation is as important as investing in projects.

- An investable project amplifies its value if it is designed to include the surrounding places it is nested within and with which it has reciprocal exchanges of value.

- Regenerative investment builds relationships between people, projects and places and their capacity to evolve and adapt.

- There is a need to assume unintended consequences over time and evolve and adapt metrics and actions.

- A regenerative project invites reflection on norms of ownership and inclusion, including the physical, mental, legal and organisational operating infrastructures that we have in place.

- Stakeholders together can establish indicators of positive impact across multiple capitals using end state thinking (how that place would be if it were operating at its best) as the benchmark against which to measure return on investment.

- When investments are invited from the local community, the benefit substantially stays within the community. Building a shared sense of belonging and local resilience is considered a key return.

- Decision-making over community investment is a social process, best agreed upon by the community and led by a trusted convenor who is embedded in the community

- Quantifying risk can tie us up in knots. There is both certainty and uncertainty in the world, and in order to realise our potential as human beings we embrace that.

Our analysis has led us to advocate for investors who are on the spot and therefore gain a more nuanced understanding of what impact is needed or possible. An investor local to the project is likely to understand the social dynamics of the project, its network of relationships and therefore the need to, and value of, investing in the process of creating generative relationships. In other words it’s not only about the ‘what’ to invest in; it’s also about ‘how’. Social processes need investment too.

While the investor enters into a direct relationship with the local land and its communities, the activator/mediator shapes projects to be regenerative by placing explicit value on the unique qualities that each actor (including the landscape) bring to the party. This opens the way for the investor to then go on a developmental journey through which they can experience their investment catalysing the potential of a local project. The activator/mediator in their turn can ask what potential would be released if this investor, investment team and invested landscape was functioning at its best.

Bioregions join things up, getting sectors like fishing, forestry, farming, energy, and water talking to each other and working on collaborative action. Collaborative action across landscapes is now the name of the game in climate adaptation. Yet in our research we were able to find only one example of financing for Nature and human economic restoration at landscape scale (and wider) in which the investors were local and a mediator/activator was given a key role.

As outlined above, the Deshkan Ziibi Conservation Impact Bond approach aims to engage and mobilise a large, diverse and committed local stakeholder group. Other examples of regenerative investment were either engaging in skilful restructuring of existing funding regimes with existing actors, or channelling finance from conventional sources. In other words, there was no additional intention to move beyond the more transactional paradigms of value creation into relational and regenerative thinking.

In their own words, the Deshkan Ziibi Carolinian Conservation Impact Bond is a ‘place-based collaboration and financial instrument to accelerate healthy landscapes in the spirit and practice of reconciliation. It builds an ethical restoration economy and restores relationships with the land while honouring Indigenous stewardship on Turtle Island. The model combines risk management, returns-based investment and financial efficiency. The social enterprise investor is local to the region’.

We were both struck in the DZCIB example by the importance the convening body—Carolinian Canada—placed on creating ‘ethical space’ for two-eyed seeing. This was a space where different world views could come together (in their case indigenous and western views) but also different paradigms of value creation. For example, regenerative agriculture advocates coming together in dialogue with stakeholders seeking carbon offsetting.

This ethical, or what we might call developmental space, is space which respects that each actor is on their own journey of learning. It is a generative and inclusive space, one that generates a field of energy that charges whole landscapes and bioregions to reach their full potential. In our next blog we will go deeper into this role of the Regeneration Activator, profiling it as an emerging profession that deserves to be called into the limelight.

Isabel Carlisle and Paul Pivcevic