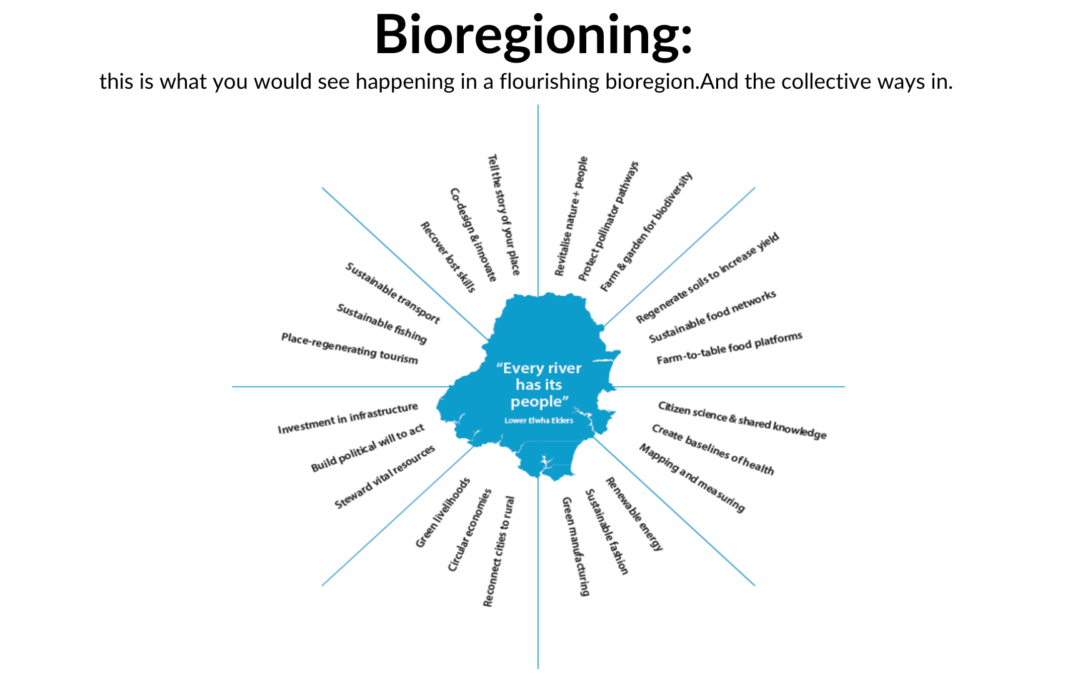

Fig 1. An example map showing indicators to track towards regenerative goals. Drawn from work by the Bioregional Learning Centre, Devon.

Part Two of Bioregions as a Framework of Value

In our last blog — a survey of our current climate change predicament and the role of regenerative investment — we posed the question: ‘Gaia is changing the rules of the (human) game. How does regenerative investment at systemic landscape scale need to respond so that human adaptation moves faster than the pace of geo-systemic change?’

We ended with an implacable equation:

Unless we can learn and adapt faster than the rate of global systems change, our viability — the basic necessities for human thriving — will dwindle to the point at which they cannot sustain us. This dynamic equation between the rate and trajectory of climate change and rate of human innovation and adaptation, with the ability to learn and take systemic, collaborative action at the fulcrum, is a lens through which to understand ‘value’ that the authors of this blog are currently exploring at bioregional scale.

In this blog post we come at this predicament from the direction of regenerative development and design. We explore what happens when we invest value in place-sourced learning, data, and governance as three interlocking pathways for adaptation. We aim to challenge investors and donors of all kinds and scales to explore the territory of regeneration with a willingness to full participation in both its returns and its implications.

We don’t lay claim to any one solution but sketch out desired regenerative outcomes and a set of criteria for landscape-scale investment that could be of use to philanthropy, venture capital and local communities. In future blogs we will suggest regenerative metrics for decision-making and also present in more detail the regenerative lens we are looking through. For now it is enough to share our ground rules for regeneration.

Whole hearted regenerative thinking and practice challenges us to work with interlocking systems, to step into a very different way of seeing the world than the default relapse into market creation, wealth extraction and business as usual. In order to meet the challenge of enabling human adaptation to move faster than the pace of geo-systemic change we need agile funding models that support this non-linear, action inquiry, approach. Wealth lies in the regenerative capability of people and place as expressed through vitality, viability and capacity to evolve.

The need for clear thinking is urgent. Even since we published our last blog in early May the rush of investors into ‘diamond class’ land-based carbon markets has come more sharply into view. As has the realisation that we are standing on the edge of a chasm, unsure how to get across it because we have failed to invest in infrastructure and know-how for bridge-building adaptation in the recent past. To give one example from the South Devon bioregion, this recent Guardian article about local biodynamic farm Huxhams Cross, run by the Apricot Centre tells how Marina O’Connell and her team transformed the soil from dry, compacted and lifeless to rich, friable and astonishingly productive in three years. Now they are training local farmers how to make that transition but it takes two to three years, resource and courage to cross that gap from industrial to regenerative farming. Meanwhile the world is facing critical food shortages.

In Scotland, landscape-scale investing in ‘rewilding’ (financed by carbon sequestration) is coming under sharp criticism for pushing up land prices and doing little to cap the carbon emissions of big fossil fuel companies and carbon-heavy businesses other than provide diamond-class carbon offsets. A new report funded by SEFARI, the Scottish Environment, Food and Agriculture Research Institutes warns that with natural capital and afforestation driving market interest and land values, without buyer checks, it is possible for highly polluting industries to reach net zero via offsetting rather than reducing their emissions at source, undermining the integrity of both markets and global political agreements. The report found more than 40 percent of farmland in the UK was bought by investors and amenity buyers over the past five years. And while land value increases provide benefits for existing owners, the authors warn this could exclude new entrants to farming, re-concentrate landownership and limit access to land by rural communities.

The impetus that is driving this well-intentioned but nevertheless default impulse back to mega market creation runs the risk of perpetuating the outmoded thinking that has got us to the point of crisis. As a critique of that thinking and a pointer to alternatives, we have looked at a number of landscape-scale regenerative projects through a lens first developed by Carol Sanford and Ben Haggard that describes four distinct paradigms of value-creation. This is a small sample from our scan.

Extract Value – in this paradigm an investor is interested largely in a single-bottom-line return on invested capital. The wider role the invested project or organisation has in relation to its beneficiaries or within its wider system is incidental aside from any direct impact on financial return. The means by which this return is achieved are of minimal importance; the focus is on opportunities for rapid scaling to acquisition.

Examples sit in the realm of business as usual and are numerous. Pick your own.

Arrest Disorder – here the basic assumption is that value is in a constant process of decay. In this investing paradigm investors profit from efficiency and optimisation: lean business operations, technology that drives efficiencies, new resource-efficient business models, or reduced resource consumption. Returns are generated through wasting less, and doing less (costly) harm.

Examples

- LENs is an independent mechanism through which businesses with a common interest in protecting the environment can work together. This approach is likely to raise the regenerative capacity of the land, but essentially supports the prevalent ‘arrest disorder’ paradigm of most business models. One current LENS project in the UK is a collaboration between Anglia Water, Nestlé and East Anglian farmers.

- Community Municipal Investments Partnership between the crowdfunding platform Abundance Investment and the public sector body Local Partnerships created Community Municipal Investments (or CMIs). This model uses investment-based crowdfunding to help local people receive a decent return for putting their money to work by supporting local green and social projects. This is not a donation-based model, which is often what people associate with crowdfunding. CMIs are backed by a business model that uses debt or equity structures to provide a meaningful financial return to those who invest.

Do Good – for investors in this paradigm ‘value’ and ‘values’ come together. Investors have a developed concept of what “good” means, reflected in values-driven vision and mission statements that set out the good they wish to achieve, and what must change or be changed in order for this goal to be achieved with a consequent improvement for people and planet.

Examples

- WWF Landscape Finance Lab supports practitioners and investors to develop sustainable landscape solutions, for example Flow Country in Scotland. This example widens the stakeholder universe when compared with the LENS example above to include the local community. The goal: a multi-use landscape where healthy and restored peatlands support globally significant biodiversity and climate protection; and a lively and prosperous region with high quality jobs. The relationship with investors is not explicitly a developmental one. Additional risks of absentee investment not connected to the particularity of the landscape.

- Working in conjunction with KPMG, Commonland calls itself an initiator, catalyst and enabler of large-scale and long-term restoration initiatives. This approach looks to achieve Four Returns: inspiration, social returns, natural returns, financial returns. In this case there is no attention to the potential sourced in the uniqueness of each landscape. The emphasis is on financialising all returns.

- The Triodos Bank recent retail investor offer of an interest bearing bond that supports a major Scottish Rewilding initiative led by Trees for Life in the Affric Highlands. The business model is investment by big business for re-wilding with pay-back in carbon sequestration and additional returns from regenerative tourism.

Regenerate Life – for the regenerative investor each landscape is a unique part of Earth’s overall ecological and geo-systemic operating system with its distinct patterning over time and therefore unique potential. To quote Ethan Soloviev: “Individual investments will vary radically from investor to investor and place to place. In one bioregion a farmers’ cooperative and food processing hub might be the key to uplifting ecosystems and livelihoods, while a rural entrepreneurship incubator and culinary agritourism cluster might energise demand and market development in another”.

Example

- The Trias Foundation in Germany has three principles: community-oriented living, acquiring and withdrawing property from speculation, and enabling and securing innovative sustainable projects

All four paradigms to one extent or another assume ‘growth’, though the more complex levels of thinking define growth in more holistic terms, beyond financial growth. This expands our normative frames around what is ‘value’ and therefore what is a ‘return on investment’. But to add another layer, the pace of change is accelerating. This is evident in ice-melt; discontinuous climatic events; and systemic global disruption across many systems simultaneously (climate, ocean water circulation, food). There is no certainty of a positive return on any investment. Can we even rely on the mantra that equities are the best performing asset over the long term? The best way we may have to manage this risk is to embrace ‘design when everybody designs’ for learning, innovating and adapting at landscape scale.

We therefore propose a reframe of ‘landscape-scale investment’. As a framework of value, bioregions offer a manageable scale for human to system relationships because in a bioregion the systems become visible and relatable (follow the link to the graphic that illustrates this blog for a downloadable PDF). Bioregioning is change at a scale that can pay attention to growing the three capacities we mentioned earlier: Vitality, Viability and Capacity to Evolve. Let’s unpack these terms:

Vitality means having the energy and health to be fully alive and present in any situation, operating with a sense of internal rootedness and a clear direction. Viability means drawing on that vitality to engage with the world around us through time: to shape and be shaped by that world. The capacity to evolve means growing ourselves and our place in tandem, becoming increasingly effective at working with complexity and joining things up. Growth in all of these in an invested project is an additional way of understanding an exchange in return for investment, but equally how we might measure a return for the investor personally or organisationally too.

How do we set meaningful benchmarks and indicators for these three capacities of vitality, viability and evolving? Deciding together at a local level, at the level of place, what these meaningful goals are and how to track progress towards them in all of these characteristics is an essentially regenerative way of creating value AND growing our capability to learn and adapt. Systems cannot evolve, cannot become more conscious, without relevant information, a community of practitioners, the will to take action around a loosely shared goal, the commitment to learn, evolve together and help each other through a self-renewing regenerative process.

In human systems, information (including data) is a key nutrient for place-sourced learning. What kind of information, who mediates it, how it is interpreted and acted upon determines the trajectory of the evolution of the system. In a self-sustaining mutual learning process actors learn from data, experience, from each other and from outside the system. Encouraging one another to step up, experiment and take action and then reflect. The overall purpose is to nudge systems towards their capacity to regenerate.

In this context, making landscape-wide decisions that involve many stakeholders is regenerative governance. Thoughtful and engaged investment could make all this possible. Changing systems is never hands off: you have to become part of the system. Changing systems has the potential to change everything and everyone implicated in the system. The return on investment is vitality, viability and the capacity to evolve – the raw materials we need in order to build the bridge over the chasm. We look forward very much to bringing these ideas into a dialogue.

Isabel Carlisle and Paul Pivcevic